The dangers of the low-fat diet

Are you still depriving yourself of the tastiest part of the chicken by removing the skin? Do you still need some convincing about the dangers of the low-fat diet? This is the final part of a 4-part series on the fallacy of the low-fat and low saturated fat diets.

In the previous post I focused on the health benefits of saturated fat. In this post I will give some more reasons why you should not be choosing low-fat options and I will give some simple guidelines on how much fat to eat.

Low fat foods and central obesity

So what happens if we manage to stick to a low-fat diet? A low-fat breakfast will cause us to crave lunch earlier and adding (saturated) medium chain triglycerides from coconut oil to a breakfast containing carbohydrates would have a particularly satiating effect when compared with longer chain saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids (1).

Low dairy fat intake has been associated with increased central obesity (belly fat) when compared with high dairy fat intake (2) and central obesity is associated with an increased risk of heart disease (3), type 2 diabetes (4) and dementia (5) as well as an increased risk of anxiety and depression (6).

Increasing carbohydrates, Alzheimer’s disease and breast cancer

When the diets of 937 elderly people were tracked for a median of 3.7 years increased carbohydrate as a proportion of total caloric intake was associated with an increased risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia, whereas increased fat or protein intake as a percentage of total caloric intake was associated with a reduced risk (7). Mild cognitive impairment is now understood to be an early stage of Alzheimer’s disease (8, 9) and the correlation with carbohydrate intake is not surprising since Alzheimer’s disease is often driven by blood sugar dysregulation and is now dubbed ‘type 3 diabetes’ (10, 11).

Dietary intake analysed for 2569 women with breast cancer and 2588 women without breast cancer found that “The risk of breast cancer decreased with increasing total fat intake whereas the risk increased with increasing intake of available carbohydrates” (12).

Fat and bile flow

Longer chain fatty acids encourage bile flow which not only aids in the absorption of fat soluble micronutrients (13) and has antifungal (14) and antimicrobial properties (15, 16), but is one of the main routes to rid your body of toxins (17, 18, 19, 20) and hormones, such as thyroid (21) and excess oestrogen (22).

This may also be why weight loss with a low-fat diet is associated with gallstone formation (23) whereas a high-fat diet reduces the risk of gallstone formation (24, 25, 26) and would thus be a safer way to lose weight. Even if you already have gallstones there is no need to go on a low-fat diet as this will not reduce the risk of the gallstones blocking your common bile duct (27).

You don’t need to search out long-chain fatty acids as most fats will contain enough long-chain fatty acids to stimulate some bile flow, and as you will see below, although bile is antimicrobial in excess it creates an environment that sulphur-reducing bacteria thrive in, as will be discussed below.

Ghee and butter contain short-chain fatty acids that will not stimulate bile flow, but they also contain plenty of long-chain fatty acids.

Coconut oil is rich in medium-chain fatty acids, more commonly known as medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), but even coconut oil has a significant long-chain fatty acid content (around 25%). If you extract the medium-chain fatty acids from coconut oil you are left with MCT oil, often used in ketogenic diets as a rapid fuel source. MCT oil will not significantly stimulate bile flow.

Dangers of the low-fat diet for fertility and pregnancy

Low-fat dairy produce may reduce fertility in women whereas high fat dairy produce may increase fertility in women (28). Insulin resistance from a high carbohydrate diet is associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) which is associated with around 30% of causes of infertility in couples seeking treatment (29).

During pregnancy women need adequate fat intake to help meet caloric needs and to avoid a low birth weight (30) which is associated with an increased risk of congenital heart defects (31), infant mortality (32) and adult obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease (33) and depression (34).

There are also greater demands on DHA and EPA during pregnancy and these long chain omega-3 fatty acids may benefit maternal mental health and reduce post-natal depression (35) as well as increase the IQ of the coming child in early life (36).

Why you need some fat tissue

Usually we are concerned with too much fat tissue but with eating disorders and certain extreme diets could too little fat tissue impact health?

Not enough adipose (fat) tissue will negatively impact metabolic health (37) and when anorexic women begin to put weight back on it tends to be in the form of inflammatory fat around the middle (38). Adipose tissue may increase your chances of survival from critical illness due to its endocrine functions (39) and possibly by acting as a buffer for toxins during illness (40). Adipose tissue may have a role in clearing excess cholesterol from the blood, as has been demonstrated in mice (41). Interestingly circadian clocks that regulate metabolism are also found in the fat tissue (42). Adipose tissue also supports fertility in women (43) and breastfeeding (44). Although belly fat has a negative impact on bone mineral density subcutaneous fat has positive effects on bone mineral density in women (45).

Finally it’s interesting that having more adipose tissue used to be a sign of health, status and beauty when calories were less readily available and now in the era of caloric abundance and the knowledge of the health risks of being overweight being slim is a sign of beauty in the Western world and this has contributed to the popularity of the low-fat diet. It is rarely appreciated that a certain amount of fat plumps out your skin and reduces wrinkles thus increasing youthfulness and beauty, as they would be commonly perceived in this age. Furthermore, as I mentioned in the previous post, total fat intake and saturated fat intake has been associated with reduced wrinkles (46).

Saturated fat and heart disease

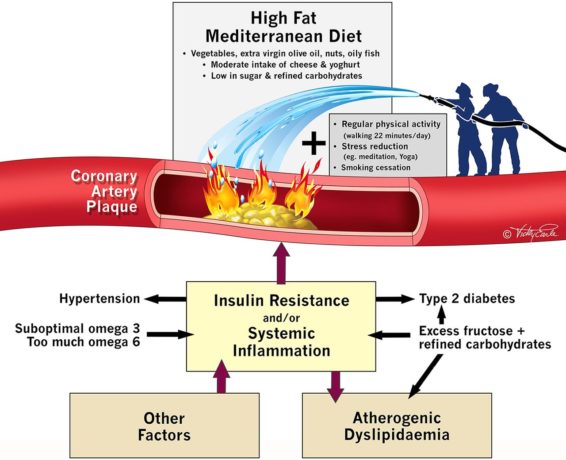

Getting back to the big issue of heart disease and saturated fat, a 2017 editorial states that “In comparison with advice to follow a ‘low fat’ diet (37% fat), an energy-unrestricted Mediterranean diet (41% fat) supplemented with at least four tablespoons of extra virgin olive oil or a handful of nuts achieved a significant 30% reduction in cardiovascular events in over 7500 high-risk patients.” (47). The editorial includes this illustration highlighting some key heart disease prevention strategies, and you can see the focus is more on reducing carbohydrate rather than fat intake:

Weight loss on a low-fat diet?

As for the advice to lose weight by adopting a low-fat diet a 2014 paper states that:

“Due to both psychological (e.g., the tendency for people to eat more of what they consider low fat) and physiological (e.g., the low satiety that accompanies carbohydrate intake) factors, reducing total caloric intake while simultaneously reducing fat intake is a difficult challenge. Further, reductions in total carbohydrate intake, increases in protein intake, and adoption of a Mediterranean diet seem to be more effective in inducing weight loss than reductions in fat intake. Traditional claims that simply reducing dietary fat will improve metabolic risk factors are also not borne out by research.” (48).

And a 2015 article in the journal Nutrition has this to say:

“Americans in general have been following the nutrition advice that the American Heart Association and the US Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services have been issuing for more than 40 years. Consumption of fats has dropped from 45% to 34% with a corresponding increase in carbohydrate consumption from 39% to 51% of total caloric intake. In addition, from 1971 to 2011, average weight and body mass index have increased dramatically, with the percentage of overweight or obese Americans increasing from 42% in 1971 to 66% in 2011….General adherence to recommendations to reduce fat consumption has coincided with a substantial increase in obesity.” (49).

Please note that I am not recommending eating huge quantities of fat. Fat tends to be satiating but too high a caloric intake is not what we evolved to deal with and the current environment of caloric abundance is believed to be a key driver behind not just obesity and type II diabetes, but also the other great killers of our time such as heart disease, neurodegenerative disease and cancer (50).

Lipid oxidation

As I explained in the previous post, polyunsaturated fatty acids are prone to oxidation (51) and yet in part 2 of this series I outlined why we need polyunsaturated fatty acids just as we need sterols such as cholesterol which can also be readily oxidised to form damaging compounds (52, 53) that can oxidise LDL particles to increase heart disease risk (54). The primary culprits to cause the damage are lipid hydroperoxides which can be elevated in your bloodstream for 2-4 hours after eating a fatty meal (55). Your body will make the cholesterol it needs so it is not simply a matter of avoiding cholesterol or polyunsaturated fatty acids, though this balancing mechanism often does not work perfectly (56) and thus is not a strong enough argument in itself for a high cholesterol diet.

The first step to protect yourself is to cook only with oils less prone to oxidation, which I have discussed in my posts Which Fats and Oils for Optimal Health?. Then you can further reduce oxidation after meals by combining fatty foods with sources of polyphenols from plant foods such as berries (57), red grapes and pomegranates, which are rich sources of flavonols, anthocyanins and procyanidins (58). It is probably the procyanidins in red wine that can also reduce the oxidation of LDL particles (59). For more information on when alcohol may or may not be beneficial please refer to my posts on hormesis. Other polyphenols that have been shown to reduce oxidative stress after meals include proanthocyanidins found in many berries and other fruits (60, 61), legumes, tea, red wine (62), grapes and cocoa (63). Virgin olive oil is rich in polyphenols that get incorporated into the LDL particle and this is likely to be how olive oil reduces LDL oxidation (64). Avocado can reduce inflammation after meals (65) though some of this effect may come from the high monounsaturated fatty acid content (66).

Cocoa polyphenols in dark (preferably 100% cocoa solid) chocolate can prevent the formation of lipid hydroperoxides in LDL particles and thus reduce heart disease risk (67) and green tea polyphenols can also reduce LDL oxidation (68). Coffee is also protective and this is probably due to the incorporation of phenolic compounds into the LDL particles (69). If you are avoiding caffeine I recommend green tea and coffee that has been decaffeinated using just water or carbon dioxide to avoid residual solvents in your beverage.

Adequate selenium intake also helps to protects the LDL particles from oxidation (70) and I recommend 200 mcg a day from foods such as seafood and organ meats (71) or 1-2 Brazil nuts a day (72) or perhaps a supplement with a variety of selenium compounds, such as a yeast-based selenium supplement.

Fat and bacterial endotoxins

An excess of low quality fats without polyphenols at the same meal can also increase the absorption of bacterial endotoxins which are highly pro-inflammatory and are a key driver of diabetes and heart disease (73). Too much saturated fat may increase the absorption of endotoxins from gram-negative gut bacteria (74, 73) though they may also have a protective effect from the endotoxins by reducing intestinal permeability as I mentioned earlier. However this increase in endotoxemia after eating saturated fat may only be significant in obese people and only when they eat large (40g) portions of fat (75). Also combining high fat with high carbohydrate high glycemic foods will increase the release of chylomicrons into the gut (76). The purpose of chylomicrons is to transport fat from your intestine, but they also transport more endotoxin into the bloodstream so please avoid combining high fat with high carbohydrate at the same meal.

Fat, hydrogen sulphide and polyphenols

Polyphenols also help to reduce another potential issue of eating long-chain fatty acids in excess, that of an overabundance of sulphur-reducing bacteria (77, 78). These generate hydrogen sulphide, which has some important physiologic functions but is toxic in excess and may be a potential driver of damage to the gut wall and inflammation leading to ulcerative colitis (79).

An excess of fats can stimulate bile which is a source of taurine, a sulphur-containing amino acid that can then increase the abundance of sulphur reducing bacteria in the gut. The resulting excess of hydrogen sulphide can damage the protective mucus lining of your gut, but these bacteria also reduce the production of short-chain fatty acids such as anti-inflammatory butyrate, which your gut flora produce from fibre, as described in the previous post. Short-chain fatty acids also decrease colonic pH and help to reduce sulphur-reducing bacteria (80), so we have a potential vicious cycle here.

Thus if you suffer from ulcerative colitis you may need to temporarily reduce your intake of dietary fat, although this should not necessarily be taken to mean that a low-fat diet is generally beneficial for most people, provided they consume enough dietary fibre for short-chain fatty acid production and sources of polyphenols to keep the hydrogen sulphide producers under control.

Polyphenols may in fact owe much of their beneficial effects not only due to reducing numbers of hydrogen sulphide producing bacteria, but also due to their ability to oxidise hydrogen sulphide itself into protective and antioxidant compounds (81, 82, 83) and also to protect the cells lining your large intestine from the harmful effects of an overabundance of hydrogen sulphide that would otherwise limit these cells ability to use oxygen (84) and hence to generate energy via cellular respiration.

Smoking benefits ulcerative colitis

The hypothesis that excessive levels of sulphur-reducing bacteria and the hydrogen sulphide they produce may be a key driver of ulcerative colitis may also explain why smoking has been well documented to benefit in ulcerative colitis, since smoking will increase blood levels of cyanide which reaches the cells lining your colon and may increase the removal of hydrogen sulphide metabolites from the gut and thus also increase the detoxification of hydrogen sulphide (85). However I suggest you seek out less harmful ways of reducing your inflammatory bowel disease. Apricot kernels may also raise blood cyanide levels (86) but there are also case reports of cyanide toxicity from consumption of apricot kernels (87, 88) and a concerning case of elevated liver enzymes without apparent toxicity (89).

Could too little hydrogen sulphide be harmful?

Not all of the research is fully in agreement on the harmful effects of hydrogen sulphide and whether it is beneficial or toxic depends largely on the dose, since if not in excess if actually seems to have a role in resolving inflammation (90) and protecting and repairing your gut lining, though it does seem to be true that it can play a role in inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease, in individuals with a genetically poor ability to oxidise hydrogen sulphide (91). I mentioned earlier that hydrogen sulphide performs some important physiologic functions, and one of these is to support nitric oxide in dilating blood vessels to reduce blood pressure, so it is interesting that a polyphenol in black tea helps to reduce blood pressure by increasing hydrogen sulphide production in your vasculature (92), but that in the gut polyphenols reduce hydrogen sulphide levels. There is also some evidence that hydrogen sulphide absorbed from your gut may contribute to the lowering of blood pressure (93, 94) and therefore might an overzealous restriction of long-chain fatty acids and sulphur containing foods such as animal protein in the diet have a negative impact on blood pressure as well as on your gut health and levels of inflammation?

Does saturated fat cause insulin resistance?

A diet very high in fat and saturated fat may reduce insulin sensitivity (95). This is because insulin receptors are embedded in cell membranes whose composition and hence fluidity reflects dietary fat intake so that when a diet high in saturated fat is replaced by a diet high in monounsaturated fat insulin sensitivity increases (96).

However a 2016 meta-analysis found that replacing carbohydrate with saturated fat had no appreciable effect on glucose regulation (97). This may in part be because one saturated fat in particular – palmitic acid – is inflammatory and causes insulin resistance (98, 99) and is readily made from dietary carbohydrate (100).

In fact blood levels of saturated fats in general are more closely related to carbohydrate intake than saturated fat intake (101). Saturated fats in your diet may only raise blood levels of saturated fat in those who are unfit although this is based on an observational study (102), which is not yet conclusive evidence. The same study found higher blood levels of saturated fats in those of higher Body Mass Index (BMI), an indication of obesity that can be skewed by athletes who may have a high BMI due to large muscle mass rather than large fat mass.

It has also been demonstrated that palmitic acid acutely induces insulin resistance in isolated muscle fibres from obese but not lean subjects. In this study the lean subjects had a mean body mass of 61kg (+/- 2.5 kg) and an average BMI of 24.0 kg/m2 (+/- 0.6 kg/m2) and in the UK a BMI of 25-30 is considered overweight so these lean subjects were not at all extremely lean, but just short of being overweight. The obese subjects had a mean body mass of 94.8kg (+/- 6.3 kg) and an average BMI of 35.4 kg/m2 (+/- 2.1 kg/m2) and in the UK a BMI of above 30 is indeed considered obese (103).

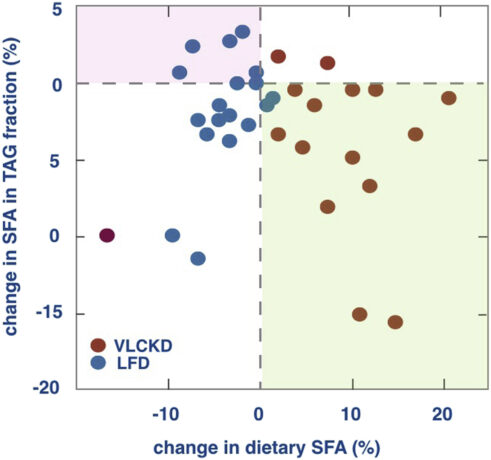

Improved insulin sensitivity is linked with improved cardiovascular health outcomes and both may be improved by partially replacing dietary carbohydrate with monounsaturated fat (104, 105). Polyunsaturated fatty acids have been found to be even more beneficial for glucose homeostasis when replacing carbohydrate, saturated and even monounsaturated fat in the diet (97), presumably in part because they will increase cell membrane fluidity, but also because both EPA, a long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid found in fish oil, and oleic acid, the predominant monounsaturated fatty acid in olive oil and avocado, have been found to reverse the insulin resistance caused by palmitic acid (106, 107), which as I have outlined may be problematic in the overweight or obese when eating a high carbohydrate diet or a high saturated fat diet if also low in cardiovascular fitness. In general, despite the exception I have just mentioned, blood saturated fatty acids are more linked with carbohydrate intake than fat intake in overweight individuals, as you can see in the image below taken from the study in which the red dots represent subjects on the very low carbohydrate diet and blue dots represent subjects on the low-fat diet, with the horizontal axis showing the change in dietary saturated fat intake and the vertical axis showing the change in blood saturated fat levels after being on one or other of these diets for 12 weeks (108). Furthermore dietary saturated fat diet has not been linked with cardiovascular disease (101), which you might surprise you if you see saturated fats as a primary driver of insulin resistance and hence heart disease.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids are prone to oxidation as I described in part 3 of this series, so despite their benefits for insulin resistance I would not consume a majority of your caloric intake from polyunsaturated fat, and monounsaturated may be the safest option to consume in larger amounts. Moreover there are several lines of argument to suggest that a first approach to improving insulin sensitivity should be to reduce carbohydrate intake (101) and 6 months of a low carbohydrate diet may lead to remission of type 2 diabetes (109).

A genetic predisposition for reduced saturated fat intake?

Aside from the overweight and the unfit, some individuals do have a genetic predisposition that means they may fare better on a diet lower in saturated fat and higher in polyunsaturated fatty acids (110). If you struggle to balance blood sugar, to reduce triglycerides or to lose weight despite your best efforts, genetic testing may be helpful to determine if your diet needs to be altered, or if there are supplements or lifestyle changes specific to your genetic profile that may help you overcome these challenges.

Alternatively you could try reducing saturated fat in your diet and replacing with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat, whilst perhaps supplementing with certified polyphenol-rich extra virgin olive oil to help reduce oxidation of the polyunsaturated fatty acids (111).

Now you may be asking if this means that saturated fats are in fact the culprit behind some individuals’ poor health. We have seen that higher saturated fat intake may be associated with insulin resistance in the obese, but does that mean that saturated fat is to blame, or does obesity create the conditions in which larger intakes of saturated fat could in fact be harmful? Or is a low intake of polyphenols to reduce endotoxin absorption to blame?

Similarly with genetics, as we learn more about how to support individuals with various genetic variants we may find that other factors are at play. For example, one gene for which variants can apparently cause poor health outcomes on a diet higher in saturated fat and lower in PUFAs is PPAR-γ (110), a transcription factor (meaning that it works by turning other genes on and off) which helps to regulate glucose and fat metabolism. Besides PUFAs (112) exercise is known to activate PPAR-γ (113, 114) and in fact individuals with this variant have a greater improvement in insulin sensitivity from regular aerobic exercise (115) so perhaps could be said to be more in need of exercise.

So if we assume a sedentary lifestyle is natural and a low intake of PUFAs is natural, then perhaps we can point the finger at saturated fat, and indeed if somebody with a genetic variant on PPAR-γ is unable to exercise for whatever reason, a lower saturated fat intake is indeed advisable. But could the poor health outcomes with this genetic variant equally be seen as due a lack of exercise, and perhaps even a lack of PUFAs, since we have plenty of evidence for the benefits of both saturated fats and of exercise in general?

I want to be clear that this is just my speculation pending further research, and I recommend testing your blood glucose, insulin and lipids with the help of a qualified practitioner to determine if you are doing enough to reduce your risk and if with your genetics you might indeed need to reduce your intake of saturated fat.

Finding the balance and tailoring your approach

Perhaps the best advice (not just for for overweight people) is to avoid very large portions of fat, to have low glycemic meals, to maintain a good level of cardiovascular fitness and to counter any inflammation with monounsaturated fat from avocado, extra virgin olive oil or avocado oil (116, 117). If you are overweight, sedentary or unfit, have inflammatory bowel disease or an overgrowth of hydrogen sulphide producing bacteria in your gut or if you find testing reveals imbalanced blood sugar or blood lipids that may be linked with your genetic profile, you may then benefit from keeping your dietary intake of both carbohydrate and saturated fat relatively low, and focus more on monounsaturated fat and protein with a moderate amount of polyunsaturated fat.

Consuming plenty of deeply coloured vegetables or other food sources of polyphenols with your meals can reduce oxidation, hydrogen sulphide producing bacteria and endotoxemia from that meal (118), one mechanism being that polyphenols bind with endotoxins (119), but polyphenols are also studied for their beneficial effects on your gut flora, which in turn may increase polyphenol bioavailability (120, 121). For more information on how to reduce your burden of inflammatory endotoxins see my posts Endotoxin, SIBO & Thyroid- A Vicious Circle and Why Chopping Your Onions Can Help You Lose Weight and for more on low glycemic meals please see Blood Sugar Balance – The Key to Health, Weight Loss and Stress Reduction.

I have already described how fats can help prevent ‘leaky gut’ so the key here is not to avoid fats, but to balance a moderate or even generous fat intake with plenty of polyphenol rich deeply coloured vegetables.

Many of my clients, especially those with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), will have fat malabsorption (as revealed by stool testing), and need to limit the amount of fat they eat to reduce digestive symptoms until the root cause of the fat malabsorption is dealt with. Also if you have gastroparesis (food sitting in your stomach for too long) or reflux then high fat meals are likely to exacerbate your symptoms (122, 123).

What I do recommend for most people is to at the very least enjoy fats as they are found in food by choosing high fat natural whole foods such as avocado, olives, nuts and seeds, organic grass-fed meat, wild oily fish and full-fat dairy produce if tolerated, as well as some additional fat in the form of extra virgin olive oil, butter, coconut oil and palm oil. This would be closer to the diet of our ancestors. Not all fats and oils are beneficial, however, and some are clearly harmful, and how they are processed and used may be harmful. Fast food has been linked with obesity and heart disease (124) and frequent consumption of fried foods is associated with increased mortality from heart disease and cancer and increased all-cause mortality (125). For more information on this please see Which Fats and Oils for Optimal Health?

What do you think about the low-fat diet and avoidance of saturated fat? Have you ever been convinced to try these dietary approaches and did they help you reach your health goals? Let me know in the comments below.

Learn more about my work in London and Totnes, or find out about online consultations.

SIGN UP TO THE NEWSLETTER TO BE NOTIFIED WHEN EACH NEW POST IS RELEASED.

Related posts:

The Low-Fat Fallacy – Saturated Fat Is Good for You – Part 1

The Low-Fat Fallacy – Saturated Fat Is Good for You – Part 2

The Low-Fat Fallacy – Saturated Fat Is Good for You – Part 3

10 Steps to Reduce Inflammation – What is Inflammation and Why Reduce Inflammation?

Which Fats and Oils for Optimal Health?

10 Reasons You Need Cholesterol – Part 1

10 Reasons You Need Cholesterol – Part 2

Hormesis – Do Toxins Make You Stronger – Part 1

Endotoxin, SIBO and Thyroid – A Vicious Circle

Why Chopping Your Onions Can Help You Lose Weight

Blood Sugar Balance – The Key to Health, Weight Loss and Stress Reduction

Leave a Reply